Agent Interaction Patterns

As our industry builds more sophisticated systems using Large Language Models, a common set of problems emerges. We’ve moved from single models answering questions to constellations of autonomous agents that need to collaborate on complex tasks. This evolution forces us to consider two distinct communication patterns: how an agent interacts with the tools and data it needs to do its work, and how it interacts with other agents.

These are different problems, and as is often the case in software design, applying a single solution to both can lead to awkward and brittle systems. In this article, I want to explore two complementary protocols that provide patterns for these different interaction axes: Anthropic’s Model Context Protocol (MCP) for agent-to-tool communication, and Google’s Agent2Agent (A2A) protocol for inter-agent collaboration.

The Agent-to-Tool Pattern

An autonomous agent is only as useful as the tools it can operate. A frequent challenge is enabling an agent to call an external API or query a database in a safe and predictable manner. Simply providing API documentation in a prompt is a crude mechanism, prone to error and difficult to secure.

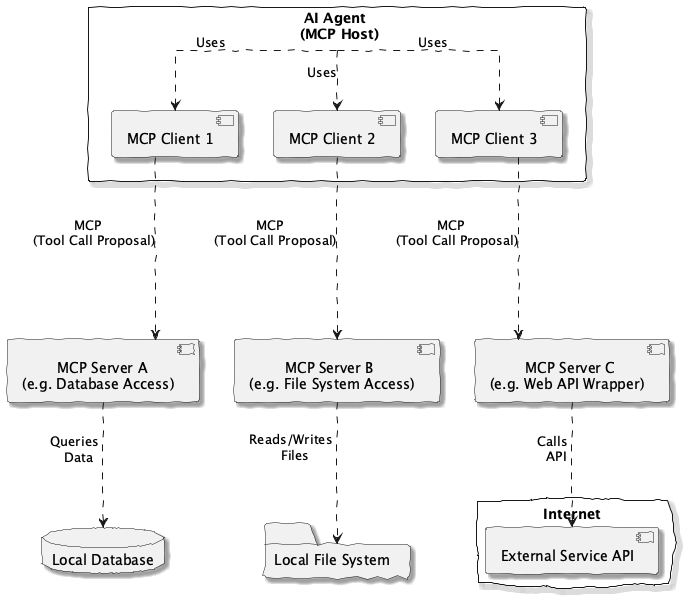

A better approach is to use a formal protocol for this interaction, a pattern I call Agent-to-Tool Communication. Anthropic’s Model Context Protocol (MCP) provides a solid implementation of this pattern. Below is a simplied archiecture overview for how it works:

A single “AI Agent” acts as the MCP Host. The agent doesn’t directly interact with data sources or APIs. Instead, it uses specialized MCP Clients to communicate with MCP Servers. The dotted arrows from MCP Client to MCP Server represent the MCP Protocol, signifying the structured “tool call proposal” and response. Each MCP Server is a lightweight program providing a specific capability. These servers then securely access the actual Local Database, Local File System, or External Service API ( such as via the Internet). This highlights the separation of concerns: the agent declares what it wants to do, the MCP Server knows how to do it and where.

The key idea is to separate the agent (the MCP Host) from the tool’s capability, which is wrapped in a lightweight MCP Server. The agent communicates its intent to the server via an MCP Client. This structure’s real value lies in its safety mechanism: the agent proposes a tool call with specific parameters. This proposal can then be approved by a human or a supervisory system before it is executed. This approval step provides a crucial authorization gate, preventing an agent from taking sensitive actions autonomously. MCP, then, is a pattern for the “last mile”—the structured, secure connection between a single agent and a single capability.

The Agent-to-Agent Pattern

The Agent-to-Tool pattern, however, does not address how multiple agents coordinate. If Agent A needs to delegate a sub-task to Agent B and monitor its progress, a different communication style is required. This is the Agent-to-Agent Collaboration pattern.

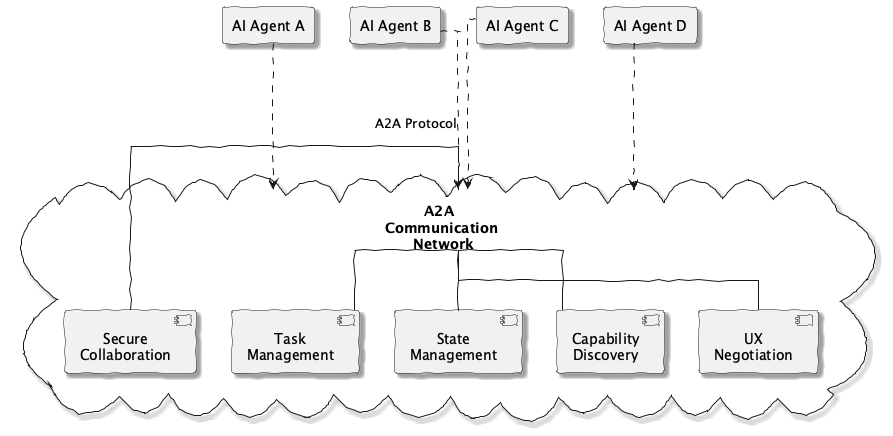

Google’s Agent2Agent (A2A) protocol is a good example of this pattern. It provides a framework for agents to communicate with their peers, enabling a set of crucial capabilities for multi-agent systems:

-

Secure collaboration: Establishing authenticated channels between agents.

-

Task and state management: Allowing for delegation, status reporting, and coordination of a task’s state across multiple participants.

-

Capability discovery: A mechanism for one agent to discover what other agents in the system can do.

A2A, therefore, isn’t concerned with how an agent uses a database; it’s concerned with how an agent asks another agent to perform a task that might involve using that database.

Complementary Patterns in a Single Architecture

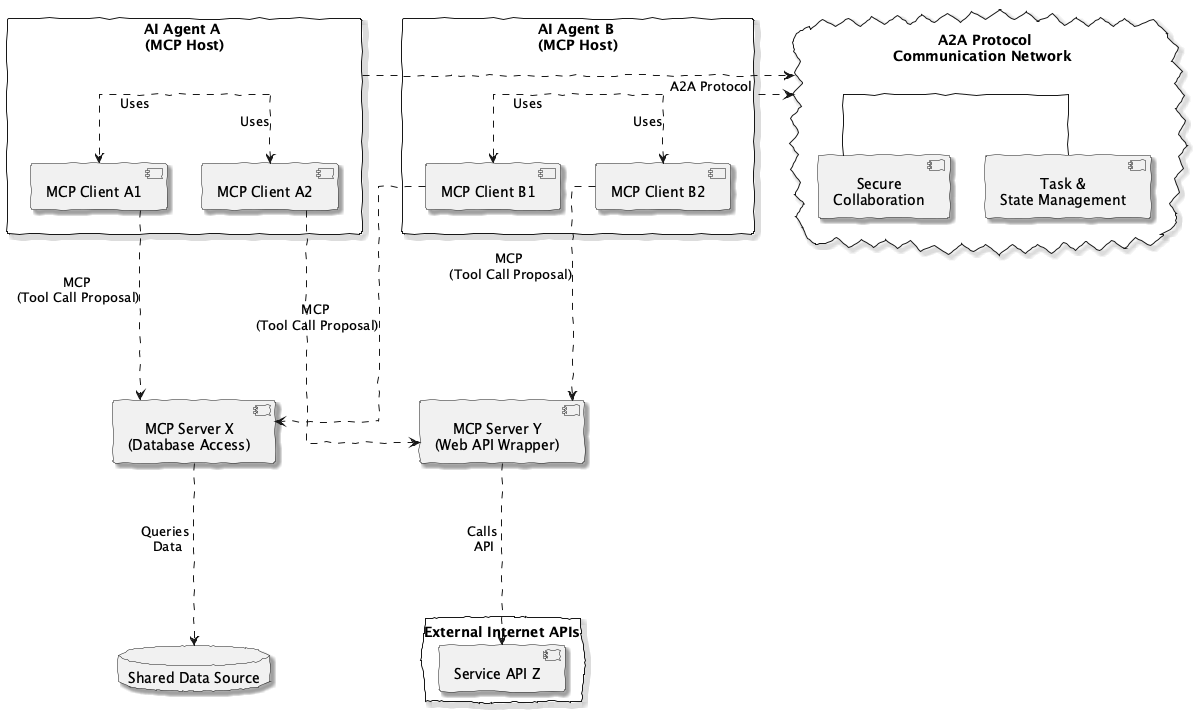

When we look at how these fit together, a clear picture may be emerging. They are not competing standards but complementary patterns for different axes of interaction. An agent uses the Agent-to-Tool pattern for its ‘vertical’ communication with data and APIs, while simultaneously using the Agent-to-Agent pattern for its ‘horizontal’ communication with its peers.

The diagram below illustrates this architecture. Each agent acts as an MCP Host, using MCP Clients to connect “down” to its tools. At the same time, the agents communicate “sideways” with each other using A2A.

I find a useful analogy is to think of a workshop. MCP provides each worker with a standardized workbench and a safe way to use their individual tools. A2A is the communication system and project management process for the entire workshop, allowing the workers to collaborate on a complex assembly.

Remaining Questions

This combined architecture, while powerful, raises important questions about cross-cutting concerns. My feeling is that while these protocols are a necessary foundation, they are not sufficient on their own for building robust, enterprise-grade systems.

For instance, achieving end-to-end observability becomes a significant challenge. If a user request is handled by a chain of three agents, each using multiple tools, how do we trace the lifecycle of that single request? A standard for propagating a trace context across both A2A and MCP interactions will be essential.

Similarly, identity propagation is a critical security problem that these communication protocols alone do not solve. If Agent A is acting on behalf of a user, Alice, and it calls Agent B, we must have a reliable way to ensure that any subsequent tool use by Agent B is still authorized under Alice’s identity and permissions.

The emergence of protocols like MCP and A2A is a sign of a maturing field. The next step in this evolution will be to build the shared platform services for observability, identity, and governance that can operate across these new standards.

And life goes on …