Knowledge Graphs in AI Memory Evolution

I’ve been using Claude regularly in my engineering workflow, and I’m genuinely impressed by its capabilities, especially when it comes to coding. When Anthropic released Claude Sonnet 4.5, the highlight for many was its performance in programming tasks. But the real innovation, I’d argue, lies elsewhere: in how the model remembers. Sonnet’s new memory system persists information as Markdown text files, a simple move but carries profound architectural implications/innovations. It signals the beginning of a transition from transient context to persistent, structured memory.

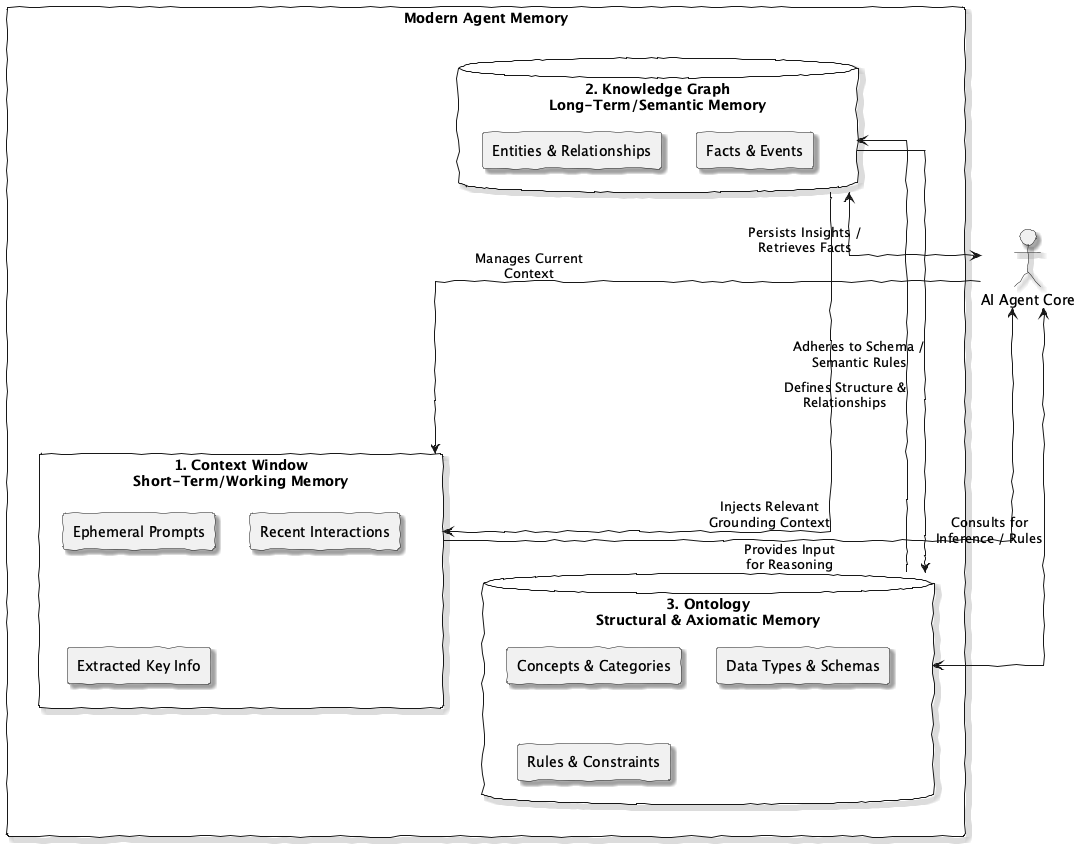

We’ve spent the last few years expanding context windows, optimizing embeddings, and refining retrieval pipelines, but all of these are temporary approaches apparently. True long-term memory will require something different: not just more data, but structure. And in both mathematics and computing, structure means graphs. In math, a graph is basically a set of nodes and edges, a formalism for representing relationships. It’s one of the most fundamental tools we have for expressing structure: what connects to what, and how those connections propagate influence. This idea was embraced fully by the computing industry. Every database schema, object hierarchy, or dependency tree can be expressed as a graph. The web itself, after all, is a directed graph of hyperlinks. When we speak of knowledge graphs, we’re simply specializing that idea .. representing not just connections, but semantics. A knowledge graph lets us say not only that two things are linked, but why they’re linked, and what that means. That layer of semantics turns inert data into something reasoning systems can traverse and manipulate. Which makes it the natural substrate for any serious attempt at long-term memory in artificial systems. Today’s language models simulate memory through context: they absorb prior turns of a conversation, compress them into embeddings, and hope the salient details survive. It’s a clever trick, but it’s still ephemeral. As soon as the context clears, the knowledge evaporates.

The next generation, hinted at by Claude Sonnet 4.5’s persistent memory move, will go further in this direction. Instead of recomputing everything each session, the model can externalize what it’s learned into a form it can later retrieve. The storage medium (Markdown files, in Anthropic’s case) is almost incidental. The important part is that the model now remembers as a process, reading and writing across time. But if we want that memory to be robust, readable, and composable, we can’t just dump text to disk and call it a day. We need structure that supports navigation and inference long term. That’s where graphs come in.

Human memory operates as a rich network of associations—where concepts are interwoven through episodes, abstractions, and analogies. When we recall something, we don’t retrieve a linear transcript, we navigate a web of meaning shaped by context and connection. AI systems are converging on the same realization. A hybrid of text, vectors, and graphs allows for richer recall than any one representation alone. Text provides narrative continuity, vectors offer fuzzy similarity, and graphs supply discrete structure, the explicit edges that make reasoning tractable.

When these elements coexist, a model can navigate memory both semantically and symbolically. It can reason about relations (“who mentored whom”), generalize across types (“projects like this one”), and retrieve by context (“documents connected to this decision”). The result isn’t just better recall, it’s emergent understanding.

Here, “text memory” captures the narrative; vector memory gives the model a way to find related experiences; and “graph memory” provides the backbone that ties everything together. So far, this hybrid architecture has lived in systems, such as RAG, vector databases, and agent frameworks like MemGPT. But we’re starting to see it move into the models themselves. Future foundation models will not just consume structured memory, they’ll contain it. That means the boundary between model and memory will blur. The model will internalize the graph’s topology, learning to compress and expand it dynamically, much as humans do when recalling a story or an idea.

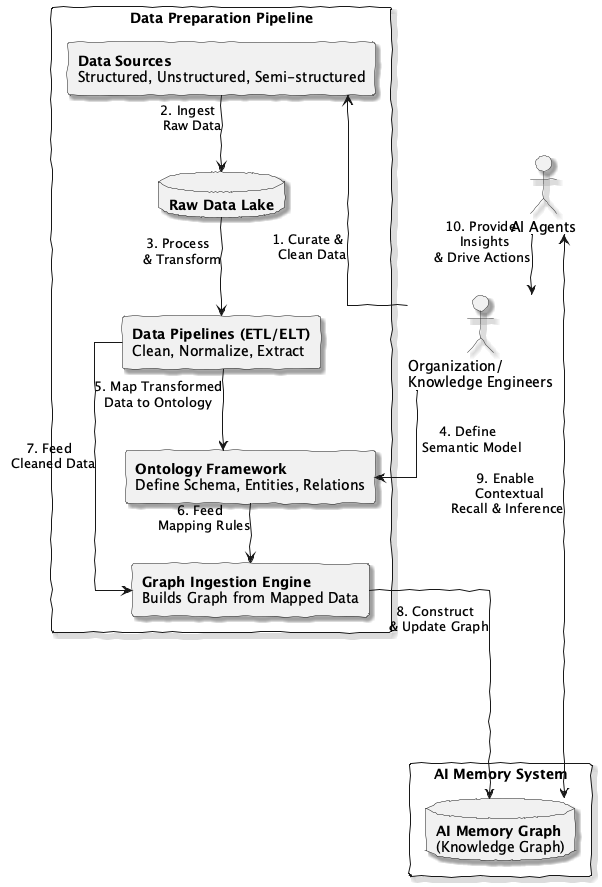

When that happens, organizations won’t simply “plug their data into an API.” like they do now. They’ll need to align their internal knowledge with the model’s internal schema. And that’s where many will stumble. Most corporate data ecosystems now are messes of files, APIs, dashboards, etc. They’re linked, but not organized. If AI systems are to integrate this information seamlessly into their memory, the data must be structured with meaning, in other words, organized around an ontology.

An ontology is more than a taxonomy. It defines not just categories, but relationships, constraints, and hierarchies. It tells the system what “is-a,” what “part-of,” and what “causes.” That context allows the AI’s graph-based memory to slot organizational knowledge directly into its reasoning fabric. The shift required is cultural as much as technical. It’s not enough to tag data or connect systems through APIs. You have to agree on what the connections mean.

The diagram above illustrates a simple flow, raw data becomes useful memory only after it passes through an ontology framework that infuses meaning.

As memory becomes a competitive feature, there’s a risk that each model vendor will build its own closed ecosystem, a “walled garden” of memory formats, schemas, and APIs. That would be disastrous for interoperability and for the open evolution of agentic AI.

We’ve seen this before: competing data formats, incompatible APIs, and costly migrations. The same mistakes repeated at the scale of AI memory could lock entire organizations into proprietary recall systems.

The antidote is, as always, open standards, shared ontologies, interoperable graph schemas, and open APIs for memory exchange. Just as the internet thrived because HTTP and HTML were open, the AI ecosystem will thrive only if its memory fabric is open as well.

Interestingly, much of what we need already exists .. in the Semantic Web. Its original vision wasn’t a static web of documents but a web of meaning, designed for agents to navigate, interpret, and act upon. Ontologies (OWL, RDF, SPARQL) were meant to capture relationships and semantics in a machine-readable way.

For years, that vision felt ahead of its time. But now, with AI agents gaining persistence and autonomy, it’s suddenly relevant again. The Semantic Web provides precisely the kind of interoperable, graph-based memory fabric that an agentic AI world requires.

If we reinterpret those technologies not as legacy curiosities but as standards for memory, we can avoid reinventing the wheel, and ensure the future of AI remains open, composable, and human-aligned.

Claude Sonnet 4.5’s memory is only the beginning. Persisting Markdown files is a baby step, but it’s the first visible trace of a deeper architectural shift: from transient context to durable, structured recollection.

Soon, we’ll watch AI memory evolve from files to graphs, from recall to reasoning, from isolation to integration. Organizations that start shaping their data around ontologies and open semantics will find themselves ready for that transition. Those that don’t will be left building bridges to someone else’s closed memory.

In software terms, this is a design moment. The decisions we make about structure and openness now will determine whether AI memory becomes a shared commons or a collection of silos. And just like in all good architecture, the shape of our data will shape the intelligence that emerges from it … And life goes on.